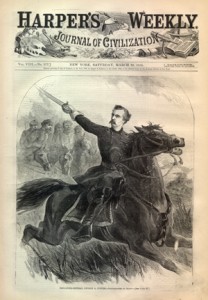

During my recent lecture on the “Era of Expansion,” I remarked that c. 1850 West Point cadets who graduated at or near the top of their class were given commissions to the Army’s topographical branch while those at or near the bottom (like the fellow you see to the left) were dispatched into the cavalry. A student (and veteran Cavalry First Sergeant) took exception to this. Appropriately skeptical, he decided to double-check my claim; in an excellent display of initiative he went straight to the source by sending off an e-mail to folks at the United States Military Academy.

Dr. Samuel Watson, Professor of Military History at the USMA and author of Peacekeepers and Conquerors: The Army Officer Corps on the American Frontier, 1821-1846 (2013), was kind enough to lend his expert insight on the issue. He’s given me permission to paraphrase his remarks:

“Cavalry” became a branch open to West Point graduates in 1833 when the Battalion of Mounted Rangers (originally formed in 1832 and officered with frontiersmen commissioned directly from civilian life) was reformed in 1833 as the First Dragoon Regiment in the Regular Army. Although, in principle, any cadet could choose cavalry, in practice class rank determined the order in which cadets made their decisions, subject to the limited number of slots available. Until the 1850s, few cadets from the top half (or even 3/4) of their class chose cavalry.

Why?

The Army’s scientifically-oriented branches were generally regarded as the most desirable commissions. Top graduates tended to gravitate toward these, especially the topographical engineers, where work on railroad, river, and harbor surveys provided opportunities to establish professional contacts that could be exploited following decommission. The Corps of Engineers, artillery, and ordnance were similarly attractive given that members were stationed disproportionately near ports along the seacoast. This meant, among other things, greater exposure to the “wider world” and a better social life. By contrast, prior to 1850 about half of officers in the Army’s mounted regiments had been commissioned directly from civilian life. West Pointers disdained them as crude and uncouth.

In the aftermath of the US-Mexican War, America’s vast territorial additions along with the continuing settlement of the Plains made service on the frontier a bit more attractive for some — particularly those who might prefer riding over intellectual pursuits. (Infantry officers had horses, but rarely got the chance to ride except for sport.) In addition, the idea of “the frontier” was gradually changing. Prior to the war with Mexico, for the vast majority of the population living east of the Mississippi, the “frontier” was associated with crude uncouth people, dark forests, and, in Florida, swamps. By the 1850s it was coming to mean adventure, freedom, space, etc. As of 1855 there were five mounted regiments in the Regular Army: First Dragoon Regiment (1833), Second Dragoon Regiment (1836), Mounted Rifles (1846), 1st and 2nd Cavalry (1855). These possessed half the number of infantry regiments and as many officers as in the four (larger) artillery regiments, so more graduates had to choose cavalry. Still, the Army’s scientifically-oriented branches continued to attract disproportionally those graduating at the top of their class.

Saving...

Saving...

Dear sir,

I am a undergraduate student in my final year writing about this exact topic. I have checked out Watson’s book. “Peacekeepers and Conqueres” but I was curious if you had any other citations that may help me with the question of westpoint perceptions of the cavalry arm. Thank you

Mr. Moran,

Thanks for your query. There are a couple contemporary journals that might be of considerable use to you. One is “Army and Navy Journal” which came out every week beginning in 1863 until 1950 when it underwent the first of several name changes. It offered a weekly look at the activities and problems of the services. I’m not sure if the individual issues are indexed anywhere but a quick search of Google uncovered some some scans of the journal. You might reprise the search to include the specific years you are interested in and then look through them online.

Probably of most useful to you (depending upon the time frame of your project) would be the “Journal of the U.S. Cavalry Association” which was published from 1888 until 1922 when it became “Cavalry Journal” (after 1946 it underwent another name change to take into account coverage of tanks – it’s now Armor magazine). This was actually the first branch specific journal to be published by the Army and had a very good reputation. I expect notes for individual articles might tell you if the author was a West Pointer or not. It also is in Google Books, at least the listing for it is – though the actual text is not there. I should think K-State would have the reprint versions of that journal as a bound volume of the journal given that it was published recently (recent being a relative term).

You might also consider contacting folks over at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth as they have/had curriculum related to Cavalry. Obviously, this doesn’t directly help you with West Point, but West Pointers often ended up there later in their careers and someone among the current crop of professional historians there might be of some help in uncovering materials.

In the event you are unaware, there is also a US Cavalry Association in Oklahoma that preserves the history and traditions of the cavalry. They are home to the U.S. Cavalry Memorial Research Library – located at Fort Reno in OK (just west of Oklahoma City) they, too, might be able to help.