Newfangled, industrial-age technologies (including rifled muskets, the Minié ball, railroads, steamboats, and the telegraph) typically take center stage in discussions of the War’s outcome, but there’s a case to be made that the Union’s success derived, in part, from its ability to supply troops with an ordinary, simple comfort: coffee.

Introduced to the US Army’s daily basic food ration in 1832 by President Andrew Jackson, coffee with sugar was seen as a cost-effective replacement for the gill (pronounced “jill”), a four-ounce (or, 1/2 cup) ration of rum or whiskey traditionally provided each day to servicemen. In 1837, Congress ordered an end to the gill on the basis of testimony from Army medical officers who noted “the substitution of coffee with sugar for whiskey…has been the means of preserving the health, efficiency, and happiness, and frequently affecting the moral reformation of…our army.”

Unknown to the medical officers at the time, there was truth to their statement. Boiling water for coffee killed off bacteria thus reducing the chance of contracting water-borne disease such as dysentery or typhoid. Even so, these remained the War’s most deadly pathogens; dysentery claimed the lives of approximately 45,000 Union and 50,000 Confederate soldiers, while typhoid struck down 35,000 and 30,000, respectively.

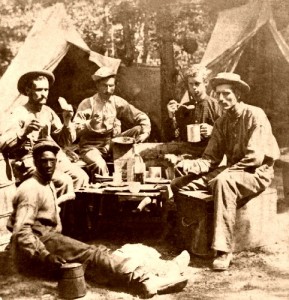

In addition to its health benefits, coffee raised soldiers’ spirits and sustained their morale. According to US Army Regulations, each company of 100 Union soldiers was entitled to receive 10 pounds of green or 8 pounds of pre-roasted coffee a day. The ration was highly treasured by troops in the field. As Orderly Sergeant Cyrus F. Boyd (Company G, Fifteenth Iowa) noted in his Civil War Diary:

No article can take the place of Coffee to the solder He carries it in a little sack in his pocket and watches it as he does his scanty pay of $13.00 per mo When the weather is cold and wet and he is deprived of this favorite beverage he becomes revolutionary and almost unmanageable With his daily allowance he will bear and forbear — but without it he may rebel at any moment

Northern troops enjoyed a more-or-less steady supply of coffee throughout the War, oftentimes drinking it with condensed milk (a new invention and superb field ration given its high content of calories, fat, protein, and carbohydrates and the fact it could be stored in tins cans for long periods without refrigeration).

Confederate soldiers were not so lucky. The Union naval blockade launched in April 1861 greatly reduced the importation of food, medicine, and other items to the Southern states. As early as 1862, coffee supplies were all but exhausted. Where, at the outset of the War, a pound of coffee cost around $3, by 1864 it was running as high as $60.

Desperate to stretch their dwindling supplies, Confederate soldiers (and civilians) cut coffee with fillers such as toasted cornmeal, rye, or chicory. When the magic beans disappeared altogether, they tried making coffee substitutes out of wheat, corn, acorns, okra, parsnips…in short, anything that could be roasted and boiled.

Parsnip coffee?

It’s amazing that the South held out as long as it did.

Saving...

Saving...

Coffee could also explain some of the crazy behavior, like running at a hundred muskets firing at you.