Although it tends to be overlooked in favor of the action that took place in the Confederate Heartland and the Virginia Triangle, the Trans-Mississippi Theater witnessed more than its share of fighting during the US Civil War.

Although it tends to be overlooked in favor of the action that took place in the Confederate Heartland and the Virginia Triangle, the Trans-Mississippi Theater witnessed more than its share of fighting during the US Civil War.

The War’s opening phase, in particular, was marked by several battles in the state of Missouri. On August 10th, the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, a major engagement pitting 12,000 Confederate forces against 5,400 Union soldiers, was barely won by the rebel army. Both sides suffered close to 1,300 casualties; among these was Nathaniel Lyon, the first Union general to die in the War. Six days later, a second, smaller clash in Lone Jack also ended in Southern victory. Although less known, a much smaller, third fight which had taken place earlier (August 5th) remains noteworthy among the Missouri encounters; it showcased three recurring elements of the Civil War: 1) fighting between family and neighbors; 2) the role of small scale skirmishing, and 3) soldiers’ desire to fight for something beyond “adventure” or “fun.” It would also prove to be the northernmost battle fought in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Founded in 1844, the town of Athens, Missouri (pronounced AY-thens) was a bustling river metropolis by the autumn of 1861. Located along the Des Moines River near the Iowa settlement of Croton, it was roughly eight miles north of present day Revere, IA. At its height Athens boasted five churches, fifty businesses, and a large hotel.

Although the Missouri legislature voted against succession in 1861, loyalties in the state were divided. Many officials and citizens remained sympathetic to the Southern cause. The most active included the Missouri State Guard, comprising former members of the state militia who joined together to coordinate resistance to Union forces stationed in Missouri. Their efforts were met by pro-Union Missourians who in turn created the Missouri Home Guard. These competing armed bands literally pitted neighbor against neighbor and fathers against sons across counties throughout the northern half of the state.

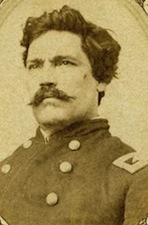

David Moore, a veteran of the Mexican-American War was elected colonel of the pro-Union 1st Northeast Regiment that formed at Kahoka, in northeast Missouri — a region whose inhabitants included many with heavily secessionist leanings. Moore’s token force of 550 was grossly outnumbered by the regional MSG. Convinced that the best defense was a good offense, he determined to strike before his opponents could fully organize.

On July 21st Moore led a combined force including his own regiment along with a mixture of Iowa and Illinois militia volunteers in a raid against the town of Etna, in Scotland County. The few State Guard troops in the area quickly scattered. Moore then withdrew to Athens where he established a headquarters on July 24th, his close to 500 men taking up residence in the town. Moore hoped that close proximity to Iowa would offer security and the possibility to call upon Iowa militia should his force be threatened.

Determined to chase off the Union occupying force, a local Colonel of the Missouri State Guard,

Martin Green raised a 2,000-man regiment. Though mostly comprised of new volunteers, Green’s forces included a cavalry command and an artillery battery, things the Union troops did not possess.

The battle was joined on August 5th. At five o’clock that morning, Union pickets on the edge of town reported the approach of the State Guard force. The first shot of the battle came from James Kniesley’s State Guard Artillery; it is reported to have travelled over the heads of the pro-Union troops, across the Des Moines River, and into the town of Croton, where it burst inside the railway depot. Short on ammunition, Kniesley’s artillery group had little impact on the unfolding battle. (Though it is worth noting that one of the field pieces used in the battle fired several iron balls through the Thome-Benning house which still stands today).

Outnumbered, surrounded on three sides, and with their backs to the river, the Union Home Guard nevertheless possessed two advantages: its men were equipped with modern rifled muskets and they knew how to use them, having received proper instruction while at Kahoka. The State Guard on the other hand was poorly trained and equipped (each man being armed with whichever revolver, shotgun, or squirreling piece he happened to bring from home). Among those attacking the town were two of Colonel Moore’s own sons.

Croton militia turned out after hearing their train station explode, but they did not cross the river and, thus, did not play an active role in the fight. Still, Athens held out for just over two hours. Green’s forces probed several times, but his men never entered the town. The battle concluded when the Major of the Confederate State Guard cavalry, Benjamin Shacklett, was shot through the neck, falling from his horse before the Union Home’s Guard left. Leaderless, the rebel forces paused. Moore immediately ordered a bayonet charge. Bluecoats poured out from the town against the secessionists. Though their numbers were small, their zeal was enough to convince Green the time had come for a general retreat.

The Confederate forces under Green lost thirty-one men killed or wounded. Moore’s Union forces reported twenty-three casualties, but in suffering these losses the Union troops had also captured twenty wounded men, along with several hundred horses. The State Guard was forced onto the defensive; it never again undertook major offensive action in northeast Missouri. Gen. Moore would later lose a leg fighting at Shiloh, but he survived the war. Green would not; he fell victim to a sniper’s bullet during the siege at Vicksburg in 1863.

Today the State of Missouri maintains the Battle of Athens State Historic Site. The park offers camping, hiking, several restored homes from the former town, and interpretive programs in season.

Saving...

Saving...