Although architecture was the last artistic field to undergo Stalinization, the imposition of the new cultural line at the First Congress of Soviet Architects (1937) left an enormous imprint on the country’s subsequent history.

Literally.

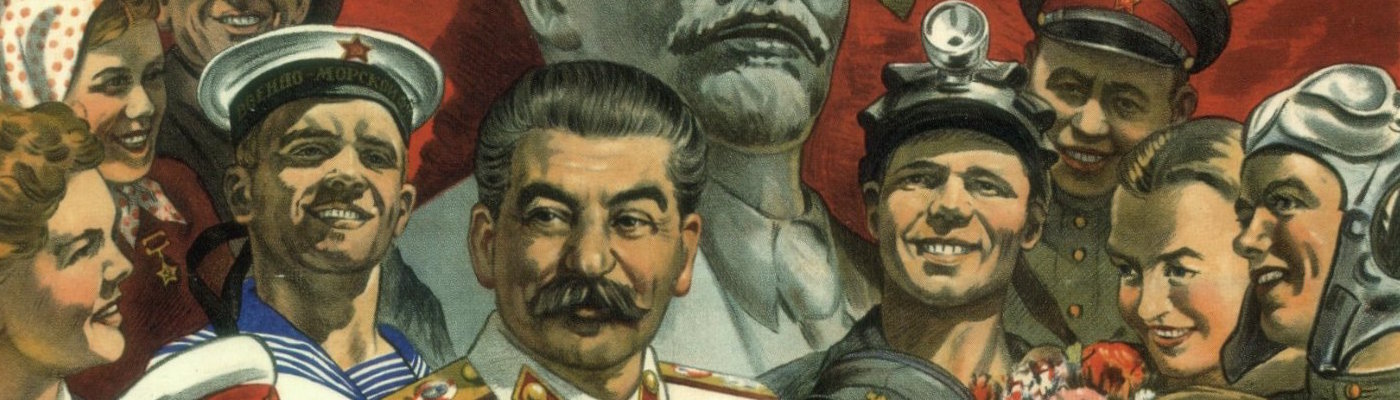

Dedicated to the monumental task of constructing humankind’s most advanced civilization and determined to showcase their progress to audiences at home and abroad, Party officials embraced architectural monumentalism as a means of demonstrating their ability to achieve modernization. Built “to reflect the power and greatness of the constructors of socialism, and to strengthen the faith of the working class in victory by organizing its will and consciousness for struggle and labor,” stupendously large buildings communicated the Party’s success in conquering space and time by enjoining ideology and aesthetics with advanced technology. Comparable to the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages, these grandiloquent icons of the dawning socialist future served as beacons of the Party’s transcendent power, inspiring both awe and a sense of purpose among ordinary believers, while providing the state impetus for the acquisition of cutting-edge methods and machinery.

First epitomized in the unrealized design for a “Palace of Soviets” (1933) to house the world Communist movement, monumental scale became the defining characteristic of the Stalinist cityscape immediately following the Great Patriotic War. Between 1946 and 1953, the colossalist impulse in architecture became manifest in concrete and steel via the so-called “Stalin skyscrapers” (Сталинские высотки) or, more colloquially, “Seven Sisters.” The largest buildings Europe had ever seen, these structures provided physical evidence of the USSR’s ability to surpass the Western powers and to call into being the Communist kingdom to come.

Saving...

Saving...

You must be logged in to post a comment.